|

The October Fair, currently ran by the Rogers family, has a long history with the town of Ledbury. A medieval charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I in the 1580s gave validity to the fair.

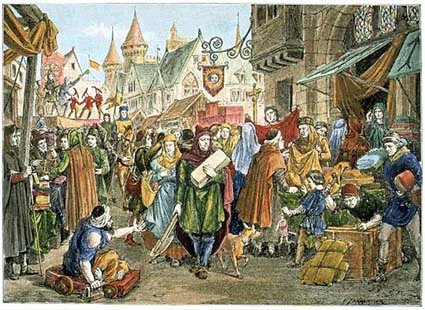

English fairs have a history going back more than a thousand years. In Roman times they were considered holidays. The medieval fair was basically a yearly market, where farmers could sell off their year's harvest, traders and merchants could meet up and sell their wares and housekeepers could buy provisions for the winter to come. For these reasons fairs were usually autumnal events.

Fairs would be lively places which brought the community together to trade and socialise. They would feature musicians, dancers, jugglers, jesters, acrobats, troubadours, minstrels and prostitutes. In Thomas Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge the protagonist famously puts his wife up for sale at a fair.

Between 1199 and 1350 about 1500 charters were issued in England for towns to hold markets and fairs. Many of these already held these events and the charter merely acted as a stamp of royal approval and to gain control of the revenues of markets and fairs for the crown.

In 1234 on 21st September (St. Matthias Day) and for the following three days Ledbury held a fair from which the Bishop of Hereford collected £7. Ledbury's charter was renewed by Elizabeth I in 1584, which allowed a weekly market and two annual fairs. The markets and fairs were granted to the Master of the Hospital in Ledbury; the cleric and parson of the rectory and the cleric and vicar of the parish church and to their subsequent heirs and successors so that:

"Their successors in perpetuity should have, hold and maintain within the town or borough of Ledbury aforesaid every year weekly during the year a market on Tuesday lasting for the whole of that day and also two fairs or mops each year, every year in perpetuity: the first fair of the said two fairs to begin on the day of the feast of the Apostles Philip and James and lasting for the whole day of that feast, and the other fair or mop of the said two fairs or mops beginning on the feast of St. Barnabas the Apostle and lasting for the whole day of the same feast."

The first of these feast days, for Apostles Philip and James, as any God-fearing catholic should know, is 3rd May. The second feast, for St Barnabas, is on June 11th. Why fairs were granted at this time in the summer and not in more convenient autumn time is not clear. The term 'mops' incidentally, according to Collins Dictionary refers to 'an autumn fair at which farm-hands and servants were formerly hired.'

The charter continued:

"We desire, ordain and decree by these presents that the Constables of the town or borough of Ledbury in office from time to time and for ever in future times should hold and administer the Court and the provision of the markets, fairs and mops aforesaid and by themselves or by an adequate deputy or adequate deputies may collect, receive and levy... without impediment from our heirs or our successors or from anyone else whatsoever, all tolls, customs, fines, amercements, profits, commodities and emoluments whatsoever as a result of the markets, fairs and mops aforesaid, or as a result of the Court of Pie Powder..."

In other words fines and profits should be collected from the fair and these should be distributed 'for the use of the poor dwelling within the said Hospital of Ledbury or elsewhere within the town or borough.'

These fines and profits would be collected by Constables and given over to the Master of the hospital, the Rector and the Vicar for distribution amongst the poor.

Nowadays the Town Council makes a charge of about a thousand pounds on the Rogers Fair and distributes the money to the good causes who write in requesting a cut of it. It is not known what the profits of the fair are, and it is unlikely that any fines raised would go into this pot of money these days.

The Court of Piepowders was set up to administer instant justice at fairs and markets across England. They would be chaired by a local man of standing they called a Steward. He would make decisions regarding law and order, settling disputes regarding such things as weights and measures, the quality of goods. He may also have collected trading tolls.

This oddly named Court is accepted as being a corruption of the Old French term pied poudre, which means dusty footed. It is thought that this described the dirty state of itinerant travelling traders who would come to the town's fair to take advantage and profit from the town's people. It has also been suggested that the court was so-called because it was set up outside on the bare ground.

The Industrial Revolution had the effect of nearly killing off fairs, but then of revitalising them. As people migrated to the urban centres accompanied by better transport systems, which also allowed food and goods to be better distributed, the fairs began to lose their raison d'etre. Thomas Frost wrote in 1874:

"[The fair has] ceased to possess any value in its so social economy, either as marts of trade or as a means of popular entertainment."

However, as the industrialised towns issued in a new age of modernity, fairs became fun fairs that mirrored and exaggerated the quicker, more chaotic and disorienting places that cities had become.

Ben Singer writes that "modernity ushered in a commerce of sensory shocks" - the thrill had been invented. In 1895 the Coney Island complex opened in USA and the future was witnessed: circular swings, loops of death, chutes, peep shows and bars.

Throughout the Twentieth Century fun fairs have provided an 'intensification of nervous stimulation' as these hyperstimulating rides and amusements have raised the bar by shocking, jolting and exhilarating us above and beyond the usual nervous energies of modern urban life.

Ledbury's street fair allows the juxtaposition between the old and new; the clash of spinning fairground rides against Tudor architecture; primary flashing colours against the black and the white; the serenity of the old market town against the noise and shock of the machines; the casual anarchy of youth against the resistence of age.

Photo: Shoko Eager

Times have changed and so have fairs. The modern fun fair has as little in common with the medieval fair of Queen Elizabeth's time, as the October dates of the Ledbury fair have to do with the Catholic feasts of Apostles Philip, James and St. Barnabus.

Sources

Translation of Queen Elizabeth's Charter 1854 [from Town Council Offices]

National Fairground Archive, Holiday City Flash and Southern Life websites.

Ben Singer in Bodies and Sensation

Ledbury: A Medieval Borough, by Joe Hillaby

This article is a revised version of October Fair: History first published on the Ledbury Portal 09/10/07

|